When Khadija Yunusa walked into the Aisami Health Clinic in Sani Mai Nagge Ward, situated in Gwale Local Government Area of Kano State, she did not expect the visit to leave her feeling unwell for the rest of the night.

Pregnant and seeking routine antenatal care, she instead inhaled thick cigarette and cannabis smoke drifting from a group of young men who regularly gathered beside the open, unfenced health facility.

“I couldn’t breathe after inhaling the smoke, and then I started vomiting immediately. My chest was tight, so I rushed out. But later that night, I vomited again and again. I was scared for my baby. That was when I decided I would never go back.”

Born and raised in Kabuga Aisami, Khadija had expected to give birth in her own community. After that experience, however, she began travelling several kilometres to Sabo Bakin Zuwo maternity hospital in Jakara, a neighbouring area.

The journey was stressful and sometimes dangerous, especially when she relied on tricycles along poorly lit roads. Yet for Khadija, it felt safer than visiting a health post with no fence, no privacy, and no dignity.

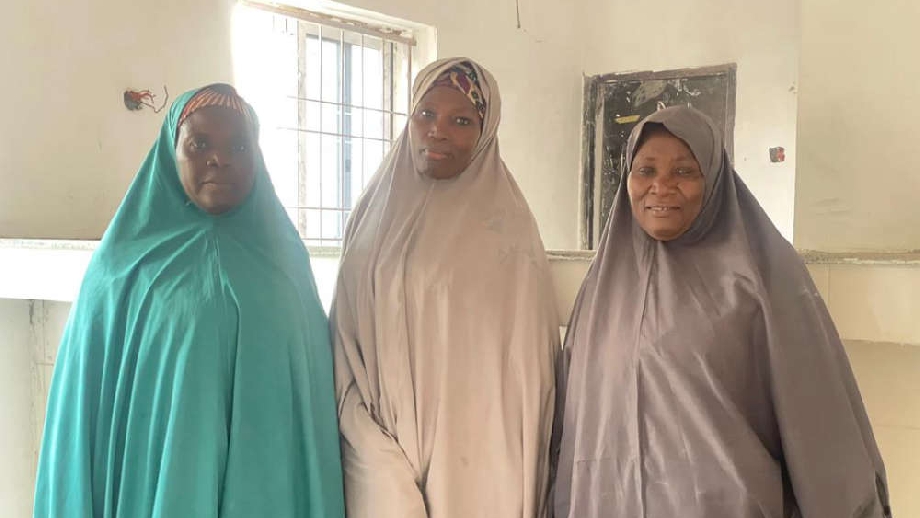

From right: Khadija Yunusa, Ashiya Mukhtar Salihu, and Habiba Ashir Dahiru

For more than 70 years, the Aisami Health Clinic had existed exactly like that: a small, ageing structure standing alone in an open field.

There was no fence to protect patients, no accommodation to keep health workers on duty overnight, and no security to prevent harassment. Behind the building, young men smoked daily - this made the women inside feel exposed and unsafe.

Then, over time, expectant mothers stopped coming. Health workers reduced their hours. A clinic meant to save lives quietly became one people avoided.

A Familiar Story Across Rural Kano

“This clinic has always been like this,” said Habiba Ashir Dahiru, a 49-year-old resident of Kabuga Aisami. “My parents brought me here when I was a baby. Now I am almost 50 years old. Nothing ever changed.”

Temporary clinic

Kabuga Aisami’s experience mirrors that of hundreds of communities across Kano State. In many rural and peri-urban areas, primary health care (PHC) centres and health posts operate for only five to eight hours a day.

Chronic shortages of nurses, midwives, equipment, electricity, water, and staff accommodation limit services.

As a result, women in labour are often forced to travel 20 to 30 kilometres, sometimes in the middle of the night to overcrowded urban hospitals in Kano city.

These journeys, often made on motorcycles over poor roads, increase the risk of complications, delays, and death for both mothers and newborns.

A National Emergency

Nigeria’s maternal health crisis provides the wider context.

According to the 2023 United Nations estimates, Nigeria is the most dangerous country in the world to give birth. One in every 100 women dies during childbirth or shortly after - about one death every seven minutes.

In 2023 alone, Nigeria accounted for roughly 29 per cent of global maternal deaths, an estimated 75,000 women. Sadly, most deaths result from preventable causes such as severe bleeding, high blood pressure, infections, unsafe abortion, and obstructed labour.

The country’s high fertility rate compounds the risk. The 2023/24 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey puts the national fertility rate at 4.8 children per woman. In Kano State, it is significantly higher at 6.8, with about 1,000 births recorded daily.

Maternal mortality in the state is estimated at more than 1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births, while child mortality stands at 103 per 1,000 live births. Only about one-third of deliveries are attended by skilled birth attendants.

Health officials say poor access to family planning, stockouts of commodities, misinformation, and cultural barriers continue to prevent families from making safer reproductive choices.

Fear as a Catalyst for Change

In Kabuga Aisami, the turning point did not come from a government programme or donor intervention. It began with fear.

In 2017, residents heard rumours that the government intended to sell the land on which the old health clinic stood. Losing the land would mean losing the community’s last remaining public health facility.

Community leaders responded by forming the Kabuga Aisami Community Initiative (KACI). They approached the then chairman of Gwale Local Government Area, Khalil Ishaq, with an unusual request: permission to build their own hospital on the site. Approval was granted.

That decision marked the start of a rare, community-driven health intervention.

Building Before Being Helped

In that same year, KACI, led by its Chairman Abubakar Ya’u, mobilised residents around a simple principle: help ourselves before government helps us.

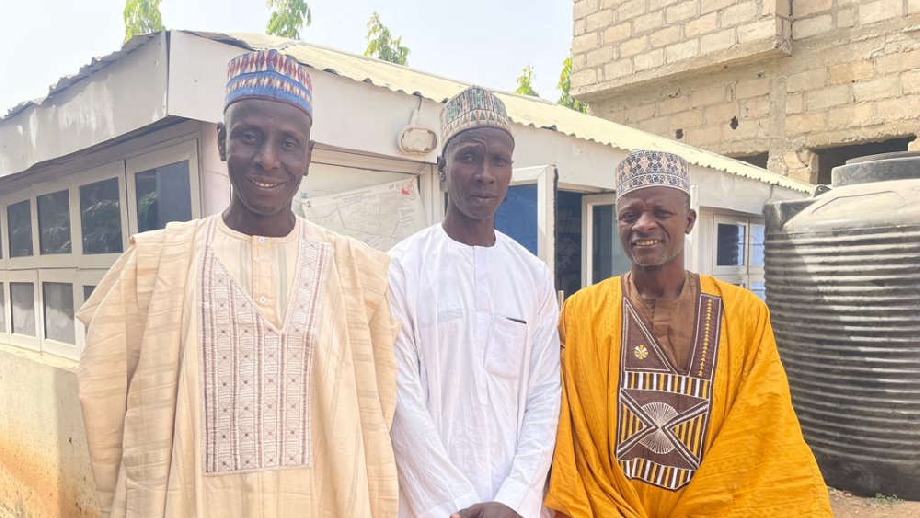

KACI chairman, Abubakar Ya’u, and secretary, Rilwanu Abubakar

The community agreed to build a one-storey hospital dedicated to women and children, naming it the Nuhu Yakubu Women and Children Hospital, Aisami, in honour of the late Nuhu Yakubu, a respected resident who made significant contributions to the development of the community over the years.

There was no external funding at the start. No NGO contracts. No donor grants. Instead, residents contributed what they could: money, sand, blocks, labour, food, and time.

Skilled artisans volunteered. Women cooked for workers. Religious leaders offered prayers.

They fenced the land to restore privacy, demolished the old health clinic, and began construction.

Designing for the Real Barriers

The community did not simply rebuild what existed before. They designed the facility around the reasons women had avoided care.

Workers during the construction of the new clinic

The hospital features two labour rooms, three wards (two paediatric and one adult), with space for 40 beds; four laboratories; and a tuberculosis treatment room.

It also has a pharmacy and offices for nurses, midwives, community health extension workers, and the Ward Development Committee. The facility has 25 toilets to improve hygiene and comfort.

Recognising that night-time services depend on staff availability, the community also built three self-contained flats for doctors within the compound. Each unit includes bedrooms, a kitchen, toilets, a parlour, and a veranda, making round-the-clock service possible.

Doctor's flats Solar-powered borehole

Water access, another long-standing challenge, was addressed when the current chairman of Gwale LGA, Alh. Abubakar Mu’azu Mojo installed a solar-powered borehole and provided water storage tanks.

Commenting on the progress, Abubakar Ya'u, chairman of KACI, stated that the community has also established a “temporary clinic within the hospital to ensure that patients continue to receive treatment and antenatal services” while the construction of the permanent structure is ongoing.

Ya’u adds that the hospital is expected to serve at least “ten surrounding communities, including Sani Menage, Me Aduwa, Warure, Ayagi, Gyaranya, Dausayi, Bakin Ruwa, Kansakali, and settlements along Goron Dutse.”

Early Evidence of Impact

Salamatu Baffa Sule, the officer in charge of the clinic, said patient numbers have risen sharply.

“Before, we attended to fewer than 200 patients a month, but now we see more than 700.”

Salamatu Baffa Sule, officer in charge of the clinic

She said women no longer sit on the floor waiting for care, skilled deliveries have increased, and health workers feel safer staying longer hours.

Khadija Yunusa, who once refused to return, now uses the temporary facility.

“It is different now, and the fence gave it a different look. When everything is completed, I will come fully.”

Habiba Ashir Dahiru, who has never seen development in the clinic for decades, says “the newly constructed hospital would further improve antenatal care attendance, especially from expectant mothers in the community.”

Ashiya Mukhtar Salihu, on the other hand, believes the hospital will significantly reduce maternal and child deaths in Kabuga Aisami and nearby communities.

“This hospital means women will not need to travel far in labour. That alone can save lives,” she said.

Why the Solution Works

During my several visits to the community, I observed that the Kabuga Aisami initiative works because it is community-owned.

Residents identified the problem themselves and designed a response that addressed not only medical needs, but also social barriers, privacy, security, dignity, and trust. Hence, the community contributions created a sense of ownership, accountability, and protection.

Also, instead of focusing first on high-cost equipment, the project prioritised infrastructure that keeps women coming and health workers present, particularly at night.

Limits and Gaps

Despite its success, the hospital is not yet complete. Doctors’ flats remain unfinished. Electrical fittings, painting, cooling systems, toilets, and some medical equipment are still lacking.

Apart from that, cigarette smoke from nearby areas remains a concern, although community leaders say the former smoking spot will be converted into a security post.

Also, the facility still faces staffing shortages and does not yet have an ambulance. According to Salamatu, a philanthropist has pledged to donate one to support emergency referrals.

Reacting, Ya’u urged the government to support the hospital with additional health workers to complement the community’s efforts. He expressed hope that the hospital would be fully completed by the second quarter of 2026.

Supporting his view, members of the community said more assistance is needed to achieve their goals. The Secretary of the group, Rilwanu Abubakar, said the community has done all it can.

“We have shown what communities can do with unity. Now we need support to complete the work, employ more staff, and sustain the services.”

Kano Government's Response

The Kano State government has acknowledged the challenges while responding to these concerns at the opening ceremony of a three-day Media Training Workshop for selected media professionals.

The workshop tagged "Advocacy Solutions to Improve PHC Service Delivery and Health Outcome aims to enhance media engagement and promote accurate and strategic reporting on critical health policies and issues, specifically.

The State Commissioner for Health, Dr Abubakar Labaran Yusuf, said, “Over 70 per cent of women in Kano still give birth at home.

According to him, many only come to health facilities when complications have already started.”

He said the state government has revived free maternal and child health services and upgraded our PHCs to provide round-the-clock services in 2025.

“We are working to provide 24/7 health service delivery in every ward, and in 2025, we upgraded over 200 PHCs. Right now, all of them are fully functional to meet this target.”

Dr Labaran stressed that the long-term goal is to make all 484 PHCs across political wards in the state operational for 24-hour service by the end of 2026 while also addressing staffing, equipment, and infrastructure improvements.”

He emphasised that the high volume of patients seeking treatment in major urban hospitals, particularly in Kano metropolis, has overstretched the available resources and personnel.

According to Dr Labaran, the state government has already begun renovations and equipment upgrades at 10 secondary health facilities in the State, adding that “the aim is to ensure that each LGA has 1 secondary health facility.”

He said, “These secondary health facilities are expected to offer improved diagnostic and treatment services once fully upgraded, thereby reducing the need for residents to travel long distances for medical care.”

The initiative, according to the health commissioner, Dr Labaran, is part of a broader commitment to strengthen the state’s healthcare infrastructure and ensure improved access to quality medical care for all residents.

Why This Story Matters

In September 2024, the Executive Director of Nigeria’s National Primary Health Care Development Agency, Dr Muyi Aina, said the country loses about 145 women of childbearing age and 2,300 children under five every day mostly from preventable causes.

Kabuga Aisami offers a rare counter-narrative: a locally led response that rebuilds trust in healthcare from the ground up.

A Model Worth Replicating

With modest funding, technical support, and policy backing, the Kabuga Aisami model could be replicated across Kano State and other parts of northern Nigeria where trust exists but infrastructure is weak.

Its central lesson is simple: when communities are empowered to lead, healthcare systems become more accessible, more trusted, and more effective.

From Smoke to Safety

The Nuhu Yakubu Women and Children Hospital is still unfinished. But it is already changing lives.

For women like Khadija Yunusa, Habiba Ashir Dahiru, and Ashiya Mukhtar Salihu, it represents something rare in Nigeria’s maternal health system - privacy, dignity, and hope.

What once drove women away with smoke is slowly becoming a place that draws them back with care.